Science

Understanding the lives and deaths of the iron coffin mummies required the generous efforts of many subject experts from a variety of disciplines, including digital scanning and radiography, physical anthropology, epidemiology, textile analysis, genealogy, and isotope analysis. Over time, this site will highlight aspects of the scientific analysis, including interviews with the scientists.

Interview with Forensic Artist Joe Mullins, 2022

Joe Mullins is a forensic artist working for the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children http://www.missingkids.com. For 23 years he has used his artistic skills and talent to help local law enforcement and the FBI in crime investigation and victim identification. In addition to his forensic work, Joe has contributed to several mummy-related projects including the facial reconstruction of four iron coffin mummies: Martha Peterson, William Pollard and Mary Camp Roberts as well as William Taylor White, a young man discovered in a Fisk mummiform coffin in Virginia a year or two before the Pollard and Robert’s discoveries. Joe has used the 3D printed skulls of William Pollard and Mary Roberts in forensic art courses he taught at the NY Academy of Art in NYC https://nyaa.edu. He also created a digital facial reconstruction of Martha Peterson as part of the Secrets of the Dead episode.

What got you interested in forensic art, and how did you make a job of it a reality?

I went to visit a friend for lunch who was working at NCMEC. I had no idea what NCMEC was. As I was being escorted to meet my friend I walked past the Forensic artists who just happened to be working on a skull approximation. Up until this point I didn’t know what a forensic artist was but I was captivated by the story of this skull and what it meant to be a Forensic Artist. I remember thinking how awesome it would be to have a job like that.

So time passed and I was asked to fill in as a temp to help out while an employee was on maternity leave. My schedule at the time wouldn’t allow it so I had to decline. NCMEC reached back out later to say it was now a full time position so I jumped at the opportunity. I was there for about 5 months and they were looking to add a 3rd forensic artist to the team. I’m fairly certain I had applied within minutes of hearing about the opening. And here I am 22 years later.

What type of course work did you have to complete?

I brought fine art and graphic design with me. I knew how to paint, sculpt, draw and use adobe photoshop. All these skills turned out to be the perfect fit to roll into the realm of Forensic Art. In my time at NCMEC. I’ve completed courses at the FBI Academy, University of Oklahoma and the University of Dundee working with the artist and anthropologist who pioneered the field.

Coming from an art background, what was the transition like from the art world to the sadness and gore you confront in your job?

Nothing can prepare you for the graphic/horrific images that come with the job. No way to erase those from your memories. Best way I can explain how to deal with it is it don’t focus on the sad but use that as fuel and passion to help bring the children home and help give victims their identity back.

Talk about the distinction between the skill/mind set necessary to do forensic art compared to non-forensic life sculpture.

As a fine artist you’re taught to express yourself in your work, paint outside the lines be creative. As a Forensic Artist one of the many challenges is keep the need to be creative in check. Very strict guidelines to follow as a forensic artist, like a train on a track you have very limited destinations once you’re on the rails you’ve got to stay on track and represent the correct face to help spark recognition.

What were your reactions when first learning that iron coffin mummies were a thing?

First experience was William Taylor White and seeing how well preserved he was after all that time was amazing. Then seeing the similarities to the living relatives was just cool.

Based on the recent discovery of the portrait of Mary Camp Roberts, talk about what it’s like to see the real face of the person you recreated.

Seeing the face of the child you’ve age progressed or the photo of a person in life to compare with the images I created is the ultimate reward as a Forensic Artist. Even if I get it wrong it’s still great to see what I did right or wrong and learn how to be better. Seeing a face from history to compare with an approximation I’ve done is, of course, very rewarding also. Amazing to see the faces side by side!

Are historical cases different than day-to-day forensic cases?

Biggest difference is these historical cases are not for identification. Not to say they are easy but it’s a different mind set going in. Much more relaxed and these typically include more detailed finishing work. Love doing wrinkles and hair and adding some character to the finished bust.

Can you talk a little about your work at the New York Academy of Art?

I began teaching that course with students working with the casts of skulls of know individuals while I worked on an actual unidentified skull from the NYC Medical Examiner’s office. Since I was working on a real skull I thought how great it would be if even the students were working on real cases also. It took many years to make that a reality. Doing that class, giving students an opportunity to use their talents to help with these cold cases, is such a high for me. I feel I’m making a difference. Like this is what I am supposed to be doing.

You work in clay and digital media; do you prefer one over the other?

Love technology and learning new ways to do things but no contest, I love the hands on sculpting. The clay under your fingernails, the smells from the classroom and building something with your hands. 100% love the fine art aspect!

How long does a typical reconstruction take?

Sculpting in clay from bare skull to finished face take about 5 days

Martha’s facial bones were severely damaged from the excavation equipment; what were the specific challenges in that case?

Having the ability to work on the CT scan of the skull to repair damage is a huge advantage. I was able to do the repairs before creating the face. I would have liked to have done a 3D sculpted bust but we were not able to get a clean enough digital file, but there was enough there to create a photo composite. Every case has it’s own set of challenges.

What are you working on now (circa 2022)?

Right now, the next big event will be the class at the NYAA in 2022 I will be working on 16 skulls from the Mutter Museum. The goal for my class has always been to clear the shelves of ME’s office across the US (and the globe) and give student artists the opportunity to work on these cold cases and make a difference … next goal is to work with museums and their skull collections to put a face to our history. So stay tuned for amazing stuff!

Where can one go to learn more about forensic art and possible career paths?

I wish I could say go check out my website … but I don’t have one. It’s a small group of Forensic Artists and full-time jobs are hard to come by … there are lots of skulls out there so contact me and I’ll do whatever I can to set you on the Forensic Art path!!

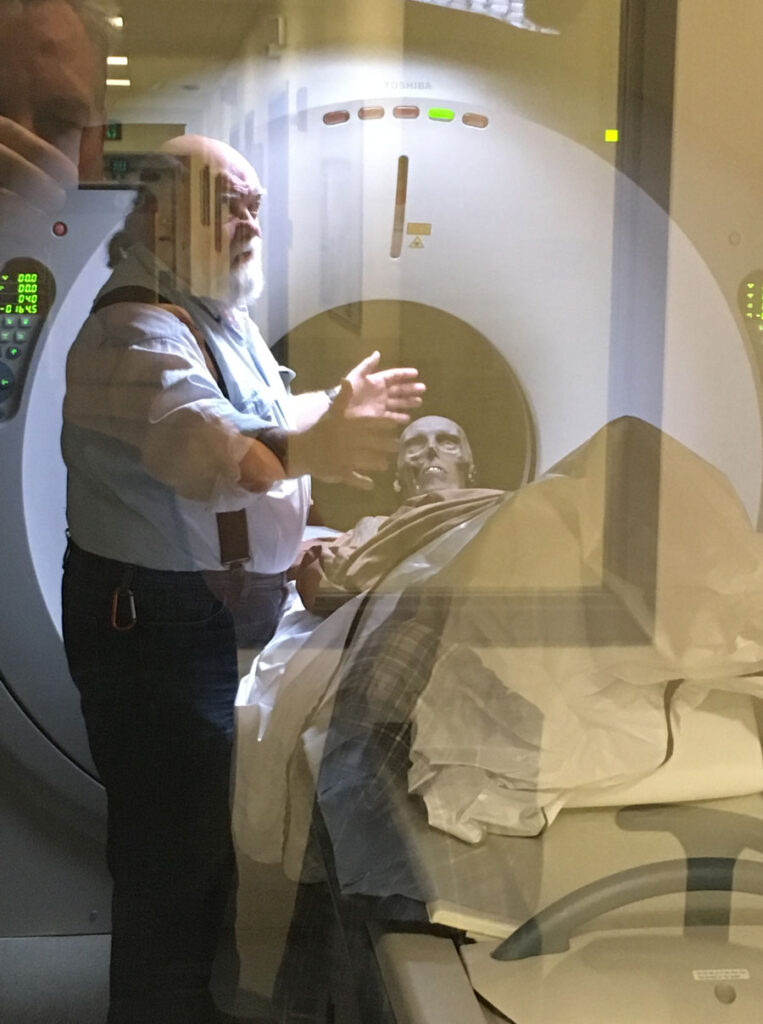

Interview with Jerry Conlogue, 2020

Jerry Conlogue was Professor Emeritus of Diagnostic Imaging and co-director of the Bioanthropology Research Institute at Quinnipiac University. He has been imaging and investigating mummies for over 30 years and has worked with hundreds of sets of mummified and skeletal remains, both human and animal, from all over the world. Jerry became involved with the Queens mummy project in 2012, contributing immeasurably to understanding the woman’s life, health, death, and even identification, as well as providing the first scans of the smallpox virus in a human body. He has generously shared some of his thoughts on this project and other aspects of his career.

What were your first thoughts when seeing the body for the first time?

Since this was the first body I had seen that had been in an iron coffin, I was amazed at the level of preservation.

How does the preservation compare to other mummies you’ve worked on?

By far it was the most well-preserved body I have had access to.

Besides mummies, what other assignments or projects have you worked on?

My research over the past 50 years has been modifying medical imaging procedures for non-medical applications. The diverse range of applications has extended from developed radiographic aging procedures for seals and whales to artistic presentations of x-rays of flowers and insects.

What are a few of your favorite cases?

This may sound a bit strange, but it is usually the case I’m working on at the moment. After all these years I still get excited beginning a new study or project. However, there have been occasions, like the Iron Coffin Lady study, when it was more than just the remains of the individual, but also the relationship with the community involved. Because I have a clinical background, to me the community represents the relatives of the individual being studied. Therefore, it has been important for me to develop a relationship with that community to insure a successful outcome. I have always attempted to involve them with a complete description of what I’m doing and to discuss all the findings. Along those lines, I’ve had similar relationships with mummified remains in Thailand and the Philippines.

For those not familiar with the different scanning technologies, can you explain the differences and benefits of the three main systems?

Plane radiographs, x-rays, are what most people are familiar with. These images can be equated to a photograph or snapshot. They are two-dimensional images of three-dimensional objects. What that means is if I’m taking an x-ray of a person’s chest from the “front”, the sternum or breastbone is superimposed over the heart and spine. Therefore, at least two x-rays are required to get a more three-dimensional impression of the structures within an object. In the case of the chest x-ray, a second radiograph must be taken from the side. With this image, the sternum, heart and spine are seen separately, but the right and left sides of the body are superimposed. Although this can be viewed as a disadvantage, the equipment can be portable and transported to the remains.

In the 1970s, another imaging modality or method to “look” inside an object was introduced. Computed tomography – CT or frequently referred to as “Cat Scan” – eliminated the problem of superimposition and presented an image of the body in “slices”. Imaging a loaf of raisin bread. If you look at the loaf from the outside, it is not possible to see the location of the raisins. However, if the loaf is sliced, the location of the raisins is clearly demonstrated. Innovations with CT equipment and software have made it possible to not only slice the “loaf” in any direction but also provide 3D-images of the intact “loaf”.

The third imaging modality, developed in the 1980s, is magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI. Instead of passing x-rays through the body and producing an image, this modality determines that quantity of hydrogen, most commonly water, in the structures under examination. Generally, mummified remains are completely dehydrated and no water remains. However, this modality also detects the hydrogen in fats that may still be present. In the case of the Iron Coffin Lady, the tissues were still “flexible,” and some signal was received from the remains – and it was possible to correlate to the CT findings.

How has this project affected your work going forward?

One finding that had been determined before the Iron Coffin Lady study is that the factors used to acquire the images must be modified from those employed with live patients. In the clinical setting, particularly with CT, the radiation dose to the patient must be minimized. In doing that, however, image resolution is sacrificed. With mummified remains, maximum resolution is necessary with a total disregard for radiation dose. Unfortunately, with the Iron Coffin Lady CT study, clinical factors were used, and the resolution was lacking. Therefore, small pox lesions may have been present on organs such as the liver, but due to lower resolution, they were not detected. Going forward, if we are using equipment at a clinical facility, I will not begin the study until I’m assured the appropriate technical factors have been set.

Do you see any new technological breakthroughs in your field on the horizon?

I’ve been in the medical imaging profession for more than 50 years. I could never have imagined the advances in the 1970s – CT – or 1980s – MRI. Therefore, I anticipate more astounding advances in the future.

What projects are you currently working on?

Since I retired in 2015, I’ve been focusing on writing up what we have done over the past 20 years. Ron Beckett and I have two books coming out in the next couple of months. In addition, we are currently working on a book about sideshow mummies and exhibited human remains.

Where can one go to learn more about digital imaging?

If you can wait for the release of our books, they will be a great resource.

More Information on paleoimaging

To learn more about paleoimaging, how it enhanced the research into the identification of Martha Peterson, and what it revealed about her case of smallpox, as well as other fascinating case studies, check out these new publications.