image from https://etc.usf.edu/clipart/62600/62694/62694_church.htm

Fisk developed his coffins at a unique period in early modern history when many traditions were being challenged, fading or replaced. By the early 1800s, American attitudes about death and burial had begun to move away from the puritanical views of the colonial period and the traditional concepts of the body, soul, life and death were giving way to the more humanistic approach. Although still a deeply religious period, the post-Revolution generations began to reject the puritanical world view and sought new paradigms and vocabulary to express their perspectives on death, mourning and memory. Many of these new ideas were introduced by recently arriving European immigrants, which began to diffuse the Pilgrim-descendant hegemony of the northeast.

https://www.courant.com/courant-250/moments-in-history/hc-250-in-memoriam-0907-20140907-story.html

https://fineartamerica.com/featured/cholera-cartoon-1883-granger.html

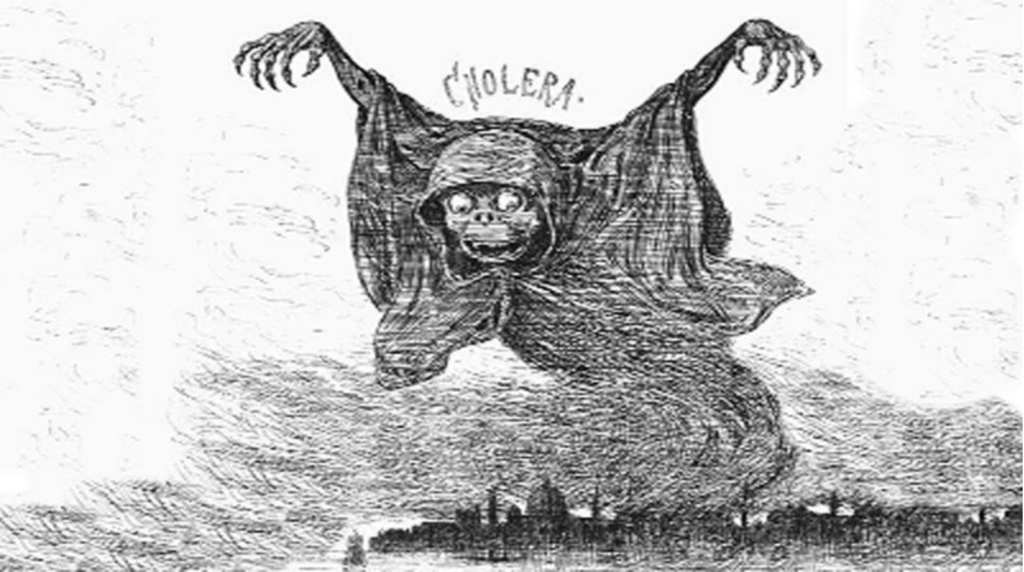

Pestilence

Outside events also began to challenge the traditional notion of death as ‘God’s Will.’ Devastating cholera epidemics, beginning in 1832, made no distinction between godly and godless or rich and poor, and killed tens of thousands over the following decades. Yellow fever and smallpox had taken their tolls, to devastating effect, in previous centuries; however, with the rise of cities and more efficient transportation, cholera had increased the death toll and misery exponentially. An outbreak in 1849 killed over 5,000 New Yorkers and 10 percent of Cincinnati’s population in a matter of months. It later killed the sitting President (Taylor) and his predecessor (Polk), within a 13-month span. The old link between sin and death was crumbling, and the sheer scale of death’s relentless presence seemed to demand a reevaluation of its meaning in American life. One example of this shift was the Rural Cemetery Movement, which set out to re-contextualize death as a fundamental part of the natural world. Even the adoption of the word cemetery, coming from the Greek word for sleeping place, attempted to take death out of the realm of the supernatural and reframe it within a more domestic, less judgmental context.

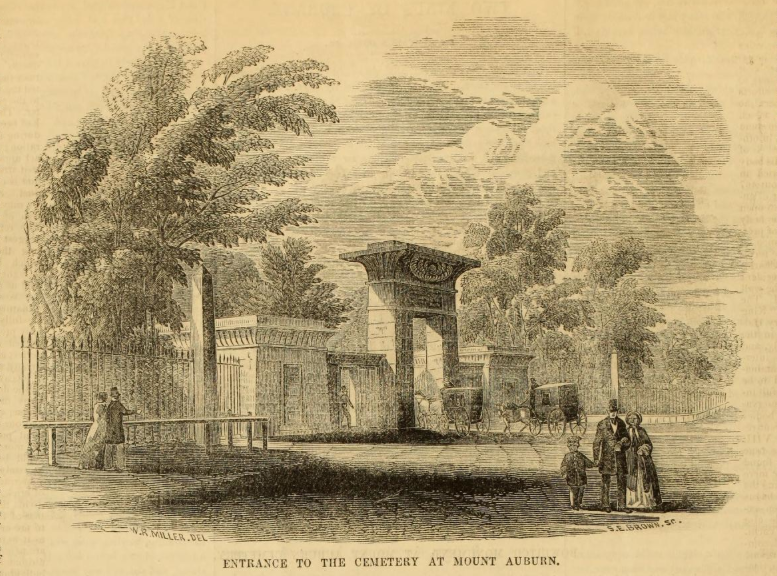

A New Kind of Resting Place

A tangible example of the movement’s philosophy is Mount Auburn Cemetery outside of Boston. Established in 1831, it’s one of the earliest examples of a burial ground in a park-like setting, and it became the model for new cemeteries throughout the country. Unlike the Puritan churchyards of the 17th and 18th centuries, which primarily reminded you that you were a sinner and would soon be dead, the visual language of Mount Auburn presented a more uplifting outlook on the inevitable. The naturalistically landscaped environment was meant to present a calming metaphor in which the living and dead were reintegrated into the circle of life, suggesting that death was just one of nature’s many mysteries to contemplate while strolling in a verdant, picturesque setting. Even the types of grave markers permitted at Mount Auburn represented a break with the past. Instead of the grimacing death’s heads and hourglasses carved into old slate, shiny marble grave markers adorned with more neutral symbols, such as urns, weeping willows or lambs, told a different story about those who lay beneath – or, more accurately, the sentiments of those who buried them.

Egypt

Mt. Auburn is also famous for its Egyptian-influenced architecture, including a monumental entrance gate adorned with a winged orb, as well as obelisks, sphinxes and pyramid grave markers and monuments. Egyptian revival style was adopted by other cemeteries, including Greenwood in Brooklyn and the Grove Street Burial Ground in New Haven. These symbols of eternity, permanence, and wisdom seemed to embody the philosophy of this new type of burial space. Although these desert-inspired sculptures may have seemed out of place in the New England landscape, Egypt, at least in the abstract, was deeply embedded in the American psyche via the Bible. By the time Fisk introduced his coffins, travel books about the Nile Valley, beginning with Napoleon’s seminal volumes on the subject, Description de l’Égypte, were bringing Egypt out of the shadows of mythology. As Richard G. Carrott explains in his book, The Egyptian Revival, Its Sources, Monuments and Meaning 1808-1858, at the time, the Egyptian Revival architectural style reflected America’s ambivalent position in the world and its need for an original identity while maintaining ties to tradition.

However, this aesthetic decision was not without its critics. For example, the Irish-born architect, James Gallier, Sr. addressed the perceived inappropriateness of Egyptian/pagan iconography in a Christian cemetery context in 1836 in his article, “American Architecture,” in the North American Review. Gallier extolled the virtue of the classical design of the Puritan meeting-house, as well as the appropriateness of the Gothic style for cemetery design, which reflects the Christian tradition. Although he approved of obelisks, he wrote that Egyptian architectural style “certainly has no connection with our religion. In its characteristics, it is anterior to civilization and therefore is not beautiful in itself.” He further opined that Egyptian architecture is… “the most degraded and revolting paganism which ever existed. It is the religion of embalmed cats and deified crocodiles …solid, stupendous, and time-defying…” and is “associated in our minds with all that is disgusting and absurd with superstition.” Although Gallier’s comments preceded the advent of Fisk’s mummiform coffins, this reaction to deviations from traditional Christian symbolism would have been a natural part of the discourse at the time Fisk unveiled his creation.

A defender of the appropriateness of the symbolism explained its natural affiliation this way: “Egyptian architecture is essentially the architecture of the grave…. Imposing and somber in its forms and mysterious in its remote origin, it seems particularly adapted to the abode of the dead, and its enduring character and contrast strongly and strangely with the brief life of mortals. Nor is it without its symbols of immortality, which the purer faith of the Christian can well appreciate and associate with the more sacred and divine promises of the gospel.” Much of this sentiment was later incorporated into Fisk’s marketing materials to great effect.

Despite protests regarding the implied pagan imagery, the coffins tapped into the zeitgeist of an age as equally fascinated with the occult and the exotic as it was with scientific innovation. Fisk’s sarcophagus-inspired Metallic Burial Cases were not only the crowning jewel of this relatively new and powerful set of funerary iconography, they also presented a paradox apropos of the time–an ancient form recreated in a modern material.

References

Bell, E. L.

1990 The Historical Archaeology of Mortuary Behavior: Coffin Hardware from Uxbridge, Massachusetts Historical Archaeology 24(3):54-78.

Carrott, R. G.

1978 The Egyptian Revival; Its Sources, Monuments and Meaning, 1808-1858. University of California Press, USA

Farrell, James J.

1980 Inventing the American Way of Death, 1830-1920. Temple University Press, Philadelphia, PA.

James Gallier, “American Architecture,” North American Review, XLIII, 93 (1836), pp. 356-384.

Habenstein, R.W. and W.M. Lamers

1955 The History of American Funeral Directing. National Funeral Directors Association. Bulfin Printers. Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Laderman, G.

1996 The Sacred Remains: American Attitudes Toward Death, 1799-1883. Yale University Press, Connecticut.

Little, B. J., Lanphear, K. M. and Owsley, D. W.

1992 Mortuary Display and Status in a Nineteenth-Century Anglo-American Cemetery in Manassas, Virginia. American Antiquity 57(3):397-418.

Rosenberg, Charles E.

1962 The Cholera Years: The United States in 1832, 1849 and 1866. The University Press of Chicago. Chicago, Ill.

Saum, Lewis O.

1975 Death in the Popular Mind of Pre-Civil War America. Death in America, David E Stannard editor. (3)30-48, University of Pennsylvania Press, PA.

Tharp, Brent W.

2003 Preserving Their Form and Features: The Commodification of Coffins in the American Understanding of Death: Susan Strasser (ed.) Commodifying Everything. pp.133-135, Routledge, New York and London.

Wolfe, S. J. & Singerman, R.

2009 Mummies in the Nineteenth Century America; Ancient Egyptians as Artifacts. McFarland & Company, Inc., North Carolina, London.