Fisk’s iron coffins are fascinating artifacts of a time when the clash between new technology and religious tradition was creating a spiritual crisis in the young country. They’re also a great example of how the unintended effects of one invention can beget new and seemingly unrelated inventions and even new industries. Iron coffins were created to mitigate some of the unforeseen negative effects that long-distance steam transportation was having on traditionally sedentary communities. The benefits of steam travel are as obvious as they are numerous; however, by the 1840s, downsides of the iron horse and river boat had begun seeping into the most private corners of American life. One unintended consequence of steam travel was its facility to enable unprecedented numbers of people to head out and potentially die far from home. Prior to refrigeration or embalming, there was no practical way to return the remains of a loved one home to be laid to rest among kin, and as a result, the deceased were often buried among strangers by strangers. This situation was considered one of the most regrettable circumstances that could befall a family during this profoundly spiritual period. A distant death denied family participation in funeral rituals and the privilege of assisting in the commencement of the greatest spiritual journey one could make. On a societal level, the absence of a funeral ceremony disrupted a central pattern of American life and weakened the bonds of local communities.

With the news of his brother William’s death in Oxford, Mississippi, in the spring of 1844, this increasingly common tragedy befell the family of Manhattan stove designer Almond Dunbar Fisk. The family deeply lamented the impossibility of retrieving William’s remains for interment in the family plot in Chazy, New York, on Lake Champlain; this reportedly hit their father, a minister, especially hard. From that moment, Fisk was determined to remedy the situation, and, uncannily, recognized that a fundamental part of the solution lay within the problem.

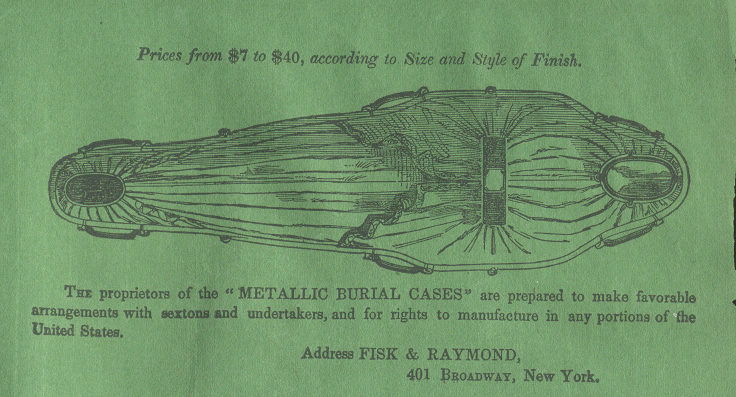

Well versed in the principles and materials of airtight stoves and boilers, the virtual heart and lungs of steam travel, he set to work refashioning a furnace into an airtight coffin capable of naturally preserving a body, which could be safely and sanitarily transported over long distances or stored for lengthy periods even in the hottest weather. In accordance with their airtight design, preservation was achieved by making the coffins as form-fitting to the body as possible, minimizing the air inside and depriving the microbes of sufficient oxygen to survive and decompose the body. Being air-tight, and thus waterproof, the coffins were also heralded as a comfort to those envisioning their loved one’s remains infested by vermin in the dark, sodden ground.

Funerals, Fame and more Funerals

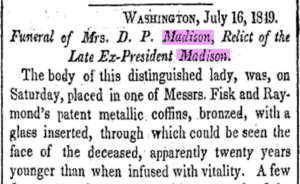

From the start, Fisk & Raymond had a shrewd business model targeting the one group that not only had a built-in need for their products but could afford them–the political elite, who typically had family burial plots in their home towns and had no desire to spend eternity buried at the swampy U.S. capital. The coffins were first displayed in the Capital’s Rotunda, where they caught the eyes of their intended audience. Fisk & Raymond gained national attention in July 1849 when the body of beloved former first lady Dolley Madison was laid out in a metallic burial case for a public viewing in D.C. Soon, many other politicians and presidents followed suite, making the coffins an item of status and prestige in the eyes of the growing middle class.

Once introduced, it became clear that Fisk’s coffins also provided a way to quarantine the remains of victims of contagious diseases, such as cholera, while still allowing for a traditional funeral and viewing. In a time before extensive use of photography, the coffin’s oval glass viewing window permitted next of kin and funeral attendees to see the person’s face and confirm the identity of the occupant without encountering odor or potential diseases. An additional selling point was as a deterrent to grave robbers, who sold corpses to medical schools for dissection. This claim is a bit ironic because, while experimenting with coffin preservation techniques, Fisk consulted with Drs. Valentine Mott and William Francis, both renowned New York surgeons who perfected their dissection skills by practicing on plundered corpses. Mott was also an avid Egyptian mummy collector and world traveler whose accounts of the tombs of the Nile may have inspired Fisk’s decision to fashion his coffins after Egyptian sarcophaguses.

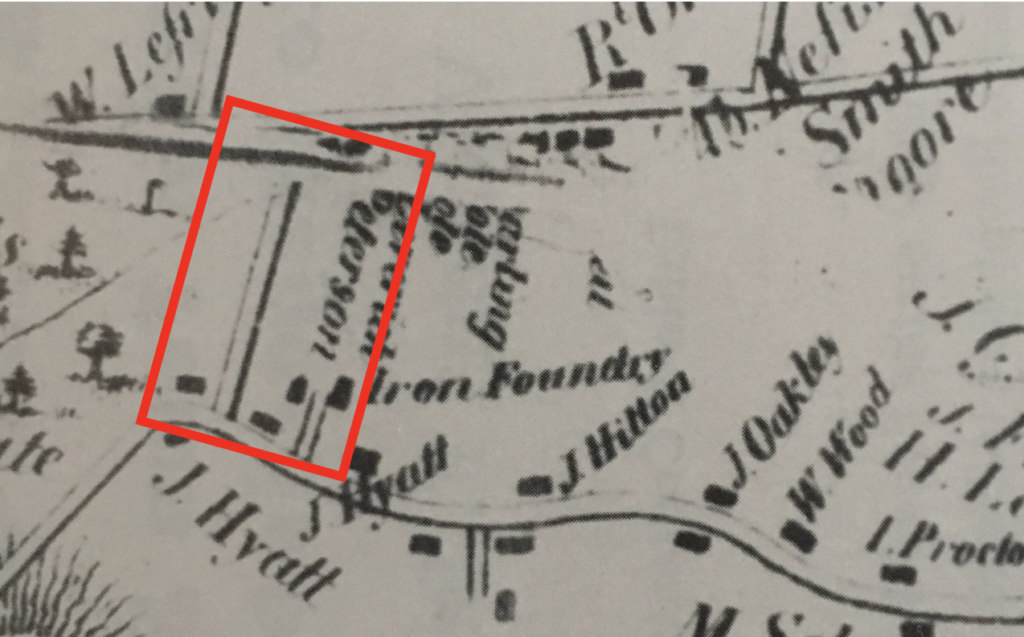

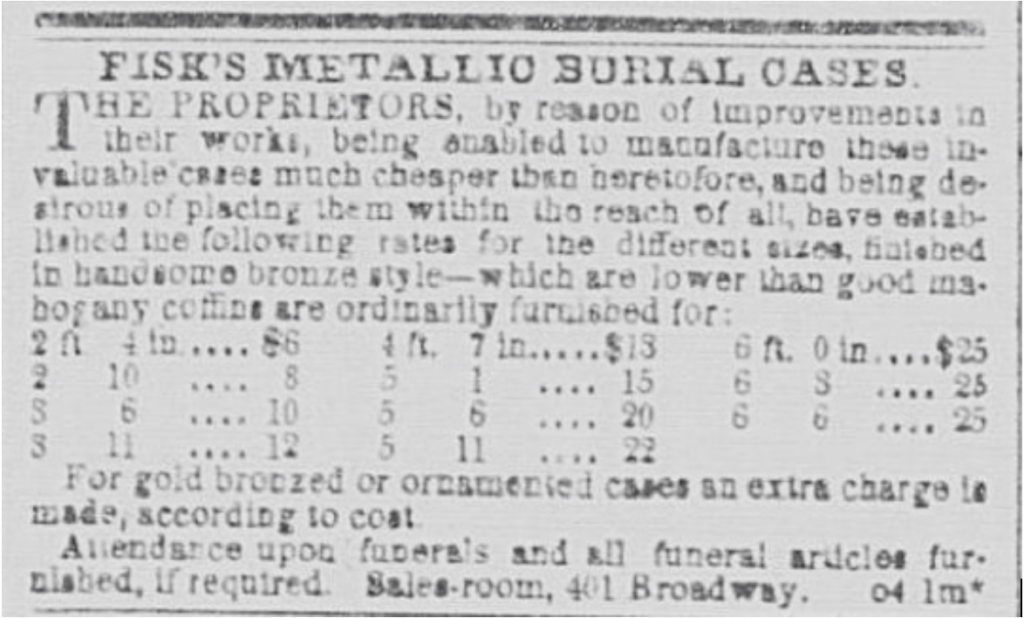

In 1845/6, the Fisk family moved from 70 Cliff Street in Manhattan to a large farm in rural Queens, and Fisk began experimentation with a small foundry furnace he built on the property. In 1846, he constructed a road across his property to enable delivery of raw materials and finished products. For many years, the thoroughfare was called Fisk Ave; today it is 69thStreet (there is still a Fisk Ave stop on the number 7 subway line north of his property). He received a patent for his ‘metallic burial case’ on November 14, 1848–just in time for the California Gold Rush. Partnering with his father-in-law, Harvey Raymond, a veteran in the shipping and foundry businesses, he formed the company Fisk & Raymond and opened a showroom at 401 Broadway in Manhattan. His stove shop at 209 Water Street, which continued to sell his patented stoves and heaters, also became the coffin shipping depot (it still stands as part of the South Street Seaport historical district). By 1850, Fisk was producing 11 sizes of coffins, ranging from 2’4” for $6 to 6’6” for $25 for basic models, which for an additional cost, could be upgraded with a fancier lining, gold bronzing and silver handles.

The high-profile funeral rocketed Fisk & Raymond to overnight fame; however, Fisk’s days of glory were tragically brief. In early September 1849, his small foundry was destroyed by a fire that consumed most of his finished stock and tools. Scrambling to finance reconstruction, Fisk offered his patent as collateral for a mortgage to Harvey’s wife’s brother-in-law, John G. Forbes, and fellow investor Horace White, both wealthy business men from Syracuse, NY, heavily involved in railroads. Working to create cash flow while rebuilding, Fisk & Raymond entered into a manufacturing licensing deal with Cincinnati stove manufacturer W.C. Davis & Co., the precursor to the celebrated rival iron coffin manufacturer Crane & Breed and Co., established a few years later. W.C. Davis began production, or at least had examples of the coffins, in time to enter and win a prize in the Ohio State Agricultural Fair in October 1850.

Despite business deals and financial support, Fisk’s luck only worsened. On October 13, 1850, 13 months after the fire, and less than two years after receiving his patent, Fisk died at age 32. The cause of death varies depending on the source–some report he died from complications resulting from saving a young boy from drowning in the East River, and the official obituary description was chronic inflammation of the lungs and bowels; however, court records related to his wife Phebe’s later claim to patent income, state that his death was a result of an illness he caught while fighting the fire. The fact that he drafted his will on January 25, 1850, suggests he had been ill enough in late 1849 to consider his condition serious. Fisk died too young, but not before achieving his goal. Thanks to his genius, it was possible to ship his body back to Chazy, where his father could conduct a funeral ceremony not afforded his brother six years earlier.

Fisk’s Iron Coffin Business Legacy

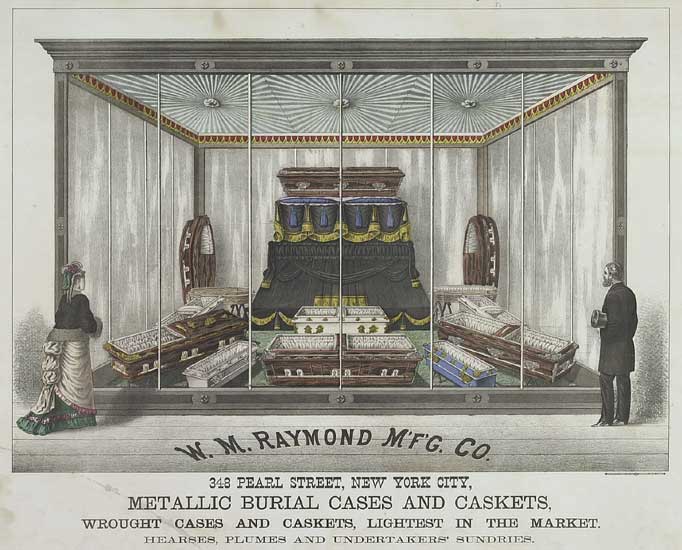

Immediately after the fire, Fisk & Raymond got to work rebuilding a much larger foundry on the north end of the property. However, even before Fisk’s death, the company was unable to pay off their debt to Forbes and White in time, which resulted in the foreclosure and auctioning off of the foundry and farm. Forbes took possession of the coffin patent and bought the properties. He subdivided the farm into what became parts of the hamlets of Winfield Junction and Locust Grove. The foundry business was renamed WM Raymond & Co., named after Harvey’s son and Fisk’s brother-in-law, William Raymond, who had been a part of the company since at least 1847. William was never the president of the company that bore his name; however, the business thrived under his day-to-day management for the next 27 years. Expanding over the years, the company provided coffins to several more presidents and congressmen, including Abraham Lincoln and his son Willie. In 1873, the company was renamed W.M. Raymond Manufacturing company–a change that represented an expansion of cast iron products, including parts for Singer sewing machines and possibly hearses. William retired in 1877 and the company was renamed the Metallic Burial Case Company; it provided caskets to the late President Garfield and King Alfonzo of Spain. The foundry closed in 1889. Although by then the iron coffin industry was in serious decline, metallic cases were still used by the military to transport those dead of contagion; however, by-and-large, the public had moved on to sheet-metal caskets similar to what we use today.

References

Allen, D. S. IV, 2002. The mason coffins: metallic burial cases in the central south. In: the 45thSOUTH CENTRAL HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY CONFERENCE, 2002, Jackson, Mississippi. http:/www.uark.edu/campus-resources/archinfo/SCHACmason.pdf.

Farrell, J. J., 1980. Inventing the American Way of Death 1830-1920

Temple University Press, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. p.3-99.

Fisk 1848, Improvement in Coffins, Letter Patent No. 5,920, Dated November 14, 1848, United States Patent Office, Washington D.C.

Fisk & Raymond, 1850. Fisk’s patent metallic burial cases, airtight and indestructible, for protecting and preserving the dead, for ordinary interment, for vaults, for transportation, or for any other desirable purpose.Printed by Robert Craighead. New York, February 1850.

Forbes, John G., 1850. Indenture for farm property made Sept. 10, 1850, Deed L85P154, Queens County Clerk’s office, Queens, New York

Forbes, John G. and White, Horace, 1849. Deed L85 P154, Liber 54 page 432. Date of instrument Sept. 10, 1849, Queens County Clerk’s office, New York.

Habenstein, R.W. & W.M. Lamers, 1956. The History of American Funeral Directing. National Funeral Directors Association. Bulfin Printers. Milwaukee, Wisconsin. P.251-310

Laderman, G., 1996. The Sacred Remains: American Attitudes Toward Death, 1799-1883. Yale University Press. P.1-85.

Little, B. J.; Lanphear, K. M. & Owsley, D. W. 1992. Mortuary Display and Status in a Nineteenth-Century Anglo-American Cemetery in Manassas, Virginia. American Antiquity57(3):397-418.

Pierce, F. C., 1896. Fiske and Fisk Family: Being the record of the descendant of Symond Fiske. Lord of the manor of Stadhaugh, Suffolk County England. From the time of Henry IV to date, including all American members of the family. Press of W. B. Conkey Company, Chicago Ill. Cornell University Library CS71 .F54

Raymond, W. M.

1847 Foundry property deed transfer,Deed L76 P421, Date of Instrument Oct 3 1847

1866 W.M. Raymond and Co. Catalog. New York

1870 W. M. Raymond and Co. Brochure. New York

Rodes, C. R., 1852. The New York City Directory, for 1851-1852, Charles Rode Publisher, New York City, New York.

Scott, R. & Hull-Walski, D.,2007. Early Metallic Coffins and Production Foundries. In: THE 40NDANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE SOCIETY FOR HISTORICAL AND UNDERWATER ARCHAEOLOGY. Williamsburg, Virginia.

Seyfried, VincentF. 1995, Elmhurst: From Town Seat to Mega-Suburb, Queens Community Series, New York.